Complex numbers

Contents

Complex numbers¶

Like the real numbers, complex numbers form what is known as a field. This means all the familiar properties of real numbers such as addition, multiplication and division adapt straightforwardly to complex numbers. In the complex number system there is a very special number called the complex unit. It is denoted \(i\) and it satisfies the curious formula,

Evidently, \(i\) cannot be any real number. A complex number \(z\) is always of the form

where \(x\) and \(y\) are real numbers. Here \(x\) is the real part of \(z\) while \(y\) is the imaginary part. Complex numbers are a combination of their real and imaginary parts.

Libary import¶

from class_scripts import cplxnums as cx

Attributes¶

In cplxnums.py we have the class cplx. Instances of cplx are complex numbers. Below are attributes of this class.

help(cx.cplx)

Help on class cplx in module class_scripts.cplxnums:

class cplx(builtins.object)

| cplx(coeffs)

|

| Methods defined here:

|

| __add__(self, other)

|

| __init__(self, coeffs)

| Initialize self. See help(type(self)) for accurate signature.

|

| __mul__(self, other)

|

| __pow__(self, n)

|

| __repr__(self)

| Return repr(self).

|

| __str__(self)

| Return str(self).

|

| __sub__(self, other)

|

| __truediv__(self, other)

|

| mtrx(self)

|

| toPolar(self)

|

| ----------------------------------------------------------------------

| Static methods defined here:

|

| __new__(cls, coeffs)

| Create and return a new object. See help(type) for accurate signature.

|

| ----------------------------------------------------------------------

| Data descriptors defined here:

|

| __dict__

| dictionary for instance variables (if defined)

|

| __weakref__

| list of weak references to the object (if defined)

|

| ----------------------------------------------------------------------

| Data and other attributes defined here:

|

| cplx_unit = [0, 1]

|

| significant_figures = 4

The class cplx passes arrays of length two, [x, y]. The first entry x is the real part and second entry y is the imaginary part. When initialised, any complex number comes with these defining properties and its norm-squared, which is \(x^2 + y^2\).

For the complex unit \(i\), its real part is 0 and imaginary part is 1. Its attrubutes are:

cplx_unit = cx.cplx([0, 1])

print(f"The real part of {cplx_unit} is {cplx_unit.re}")

print(f"The imaginary part of {cplx_unit} is {cplx_unit.im}")

print(f"The norm squared of {cplx_unit} is {cplx_unit.normsq}")

The real part of 0 + 1i is 0

The imaginary part of 0 + 1i is 1

The norm squared of 0 + 1i is 1

Note that we have printed the complex unit above as 0 + 1i. This is due to our modification of __str__. In raw form, the complex unit is represented as:

print(repr(cplx_unit))

cplx([0, 1])

Complex number generator¶

The following code generates instances of complex numbers with integral real and imaginary parts. It passes in amt, the amount of complex numbers to generate and rng, the integer range to sample for real and imaginary parts.

from random import randint

def generateCplx(amt, rng):

cplx_nums = []

for _ in range(amt):

re = randint(rng[0], rng[-1])

im = randint(rng[0], rng[-1])

cplx_nums += [cx.cplx([re, im])]

return cplx_nums

Below is a list of 10 complex numbers with integral real and imaginary parts between -10 and 10. Their norm-squared is printed alonside.

amt = 10

rng = [-10, 10]

cplx_num_lst = generateCplx(amt, rng)

for num in cplx_num_lst:

print(f"For {num} its norm-squared is {num.normsq}")

For 2 + 0i its norm-squared is 4

For 9 + 4i its norm-squared is 97

For -2 - 4.0i its norm-squared is 20

For -7 - 3.0i its norm-squared is 58

For 2 + 1i its norm-squared is 5

For -8 - 2.0i its norm-squared is 68

For -6 - 6.0i its norm-squared is 72

For -2 - 8.0i its norm-squared is 68

For -1 - 2.0i its norm-squared is 5

For 3 + 5i its norm-squared is 34

Arithmetic¶

Complex numbers can be added, multiplied, subtracted and divided. Modifying the relevant the dunders allows for adapting +, *, -, / to instances of cplx. To illustrate, for the following two complex numbers

we will return:

\(z_1 + z_2\);

\(z_1 - z_2\);

\(z_1 \cdot z_2\);

\(z_1/z_2\).

cplx_1 = cx.cplx([-2, 4])

cplx_2 = cx.cplx([4, -1])

print(cplx_1 + cplx_2)

print(cplx_1 - cplx_2)

print(cplx_1 * cplx_2)

print(cplx_1 / cplx_2)

2 + 3i

-6.0 + 5.0i

-4.0 + 18.0i

-0.7059 + 0.8235i

Note

Decimal places are reported to 4 significant figures.

Integer powers¶

With multiplication comes power. The dunder __pow__ allows for adapting ** to instances of cplx. As an illustration, below are the first 5 powers of the complex unit i.

for i in range(5 + 1):

print(f"The {i}-th power of {cplx_unit} is: {cplx_unit**i}")

The 0-th power of 0 + 1i is: 1 + 0i

The 1-th power of 0 + 1i is: 0 + 1i

The 2-th power of 0 + 1i is: -1.0 + 0.0i

The 3-th power of 0 + 1i is: 0.0 - 1.0i

The 4-th power of 0 + 1i is: 1.0 + 0.0i

The 5-th power of 0 + 1i is: 0.0 + 1.0i

Matrix representation¶

Preliminaries¶

It is possible to study complex numbers without ever mentioning the complex unit \(i = \sqrt{-1}\) and instead only considering real numbers. But what we gain in doing so is conceded by having to deal with matrices.

To see why matrices are relevant, recall that any complex number \(z\) is specified by two real numbers \(x, y\). The correspondence \(z \mapsto (x, y)\) gives an isomorphism of sets \(\mathbb C\cong \mathbb R^2\). As the complex numbers form a field we have the operation of multiplication \(\mathbb C\times \mathbb C \rightarrow \mathbb C\). Equivalently (or rather, dually), any complex number \(z\) can be thought of via the multiplication \(z : \lambda \mapsto \lambda \cdot z\). Hence any complex number is a transformation \(\mathbb C \rightarrow \mathbb C\). Note that it is linear since \(a\lambda \mapsto (a\lambda) z = a(\lambda z)\). Hence moreover, any complex number will be a linear transformation. Using that \(\mathbb C\cong \mathbb R^2\), we deduce that any complex number can be thought of as a linear transformation \(\mathbb R^2 \rightarrow \mathbb R^2\), i.e., as a \(2\times 2\) matrix.

Explicitly, with \(z = x + yi\), this \(2\times 2\) matrix representation is

Let \(M(z)\) denote the matrix representation of \(z\). The unit \(1\) and complex unit \(i\) are represented respectively by,

A straightforward calculation will show for two any complex numbers \(z_1, z_2\) that \(M(z_1z_2) = M(z_1)M(z_2)\). Hence that \(M : \mathbb C \rightarrow \mathrm{GL}_2(\mathbb R)\) defines a representation of the complex number field \(\mathbb C\) on the group of \(2\times 2\), real matrices.

Note

The representation \(\mathbb C \stackrel{M}{\rightarrow} \mathrm{GL}_2(\mathbb R)\) is “faithful”, i.e., injective, since \(M(z) = 0\) if and only if \(z = 0 + 0i\).

Implementation¶

The class cplx in the module cplxnum.py contains the method mtrx(). Calling this on any instance of cplx, i.e., on any complex number \(z\), returns its matrix representation \(M(z)\). To illustrate, for the following complex numbers:

\(1 + 0i\);

\(0 + 1i\);

\(-3 + 5i\)

their matrix representations are:

unit = cx.cplx([1, 0])

cplx_unit = cplx_unit

cplx_3 = cx.cplx([-3, 5])

cplx_nums_to_rep = [unit, cplx_unit, cplx_3]

for cplx in cplx_nums_to_rep:

print(cplx.mtrx())

[[1 0]

[0 1]]

[[ 0 -1]

[ 1 0]]

[[-3 -5]

[ 5 -3]]

Note

For any instance of cplx, the matrix representation method mtrx() returns a numpy array.

Recovering attributes¶

From the matrix representation of a complex number \(z\), its real and imaginary parts can be ontained as follows. Recall that the trace of a matrix is the sum of entries on its diagonal. Hence with \(z = x + yi\) see that \(\mathrm{tr}~M(z) = 2x\). The real part of \(z\) is therefore \(\frac{1}{2}\mathrm{tr}~M(z)\).

As for the imaginary part it is necessary to first multiply by \(-i\). This has the effect of rotating real and imaginary to imaginary and real. The imaginary part of \(z\) is therefore \(\frac{1}{2}\mathrm{tr}~M(-zi)\). Since we know \(M(z_1z_2) = M(z_1)M(z_2)\), we can obtain the imaginary part equivalently by \(-\frac{1}{2} \mathrm{tr}(M(z)M(i))\).

Concerning the norm squared attribute, it can be recovered as the determinant of the matrix representation. That is, if \(\|z\|^2\) denotes the norm-squared of the complex number \(z\) then

This makes it clear that the length of a complex number can be related to an area spanned by real vectors in two dimensions. We leave it to the intrepid reader of these documents to test these claims using the class cplx.

Polar coordinates¶

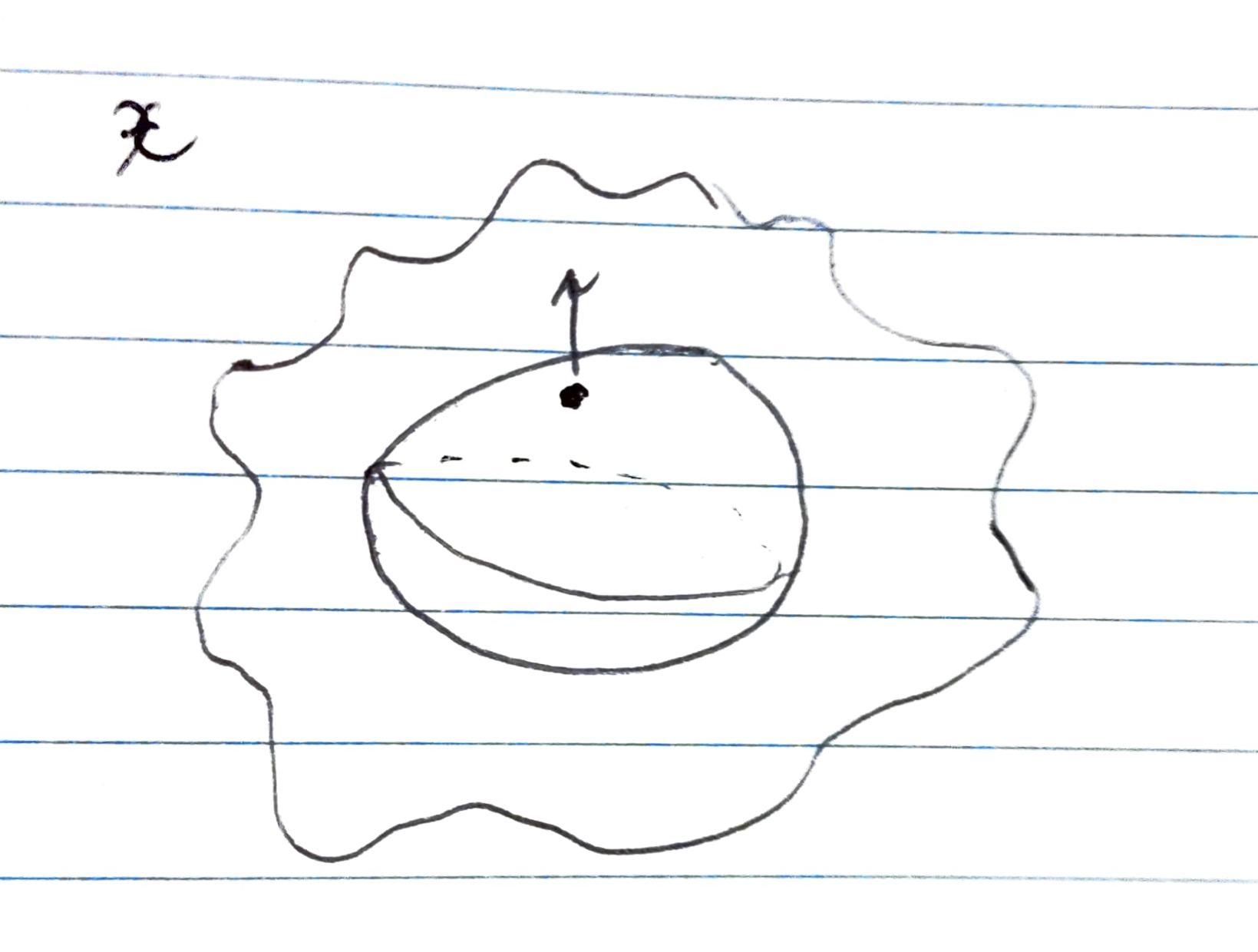

With an isomorphism \(\mathbb C \cong \mathbb R^2\), two important reference objects are defined: a pole and axis. The pole here is the origin \((0, 0)\); the axis is the \(x\)-axis. Through these objects, any complex number when mapped to a vector in \(\mathbb R^2\) can be faithfully represented by:

its distance from the pole, \(r\);

the angle it makes with the \(x\)-axis, \(\varphi\).

The image of a complex number in the \((r, \varphi)\)-plane is referred to as its polar representation.

Note

The distance \(r\) is necessarily positive.

Polar transformation¶

The mapping of \(z\) onto the polar coordinate plane is referred to as a polar transformation. For \(z = x + yi\), it maps onto \(\mathbb R^2\) by \(z\mapsto (x, y)\). The polar transformation is obtained by specifying where the real and imaginary parts map to in the \((r, \varphi)\)-plane. Since \(r\) is the distance to the pole, which in this case is the origin, see that

With \(r\) known, the angle \(\varphi\) made by \(z\) and the \(x\)-axis is given by

Implementation¶

The method toPolar(), callable on any instance of cplx sends a complex number to its polar representation. Recall the complex numbers from earlier:

\(1 + 0i\);

\(0 + 1i\);

\(-3 + 5i\).

Their polar representations are:

for cplx_num in cplx_nums_to_rep:

print(cplx_num.toPolar())

(1.0, 0.0)

(1.0, 1.5707963267948966)

(5.830951894845301, 2.1112158270654806)

Polar coordinates are a convenient coordinate system to express, model and graph complex systems and functions. In a forthcoming section on complex functions we will return to polar coordinate representations as a means to visualize and graph functions.

Fractional powers¶

Preliminaries¶

The polar transformation sends any complex number \(z\) to a radial and angular coordinate \((r, \varphi)\). This reflects the alternate representation of any complex number,

With \(z = x + yi\), Euler’s identity states \(x = r\cos\varphi\) and \(y = r\sin\varphi\). That is,

The utility of this formula lies in calculating fractional powers of complex numbers. For any fraction \(a/b\) we have

where \(r^{a/b}\) is the fractional power of \(r\) which, recall, is a real number.

Implementation¶

In cplxnums.py the function powFrac() passes instances of cplx and a rational number. It returns their fractional power. To illustrate, consider the following complex number,

A fifth root, \(z^{1/5}\), is:

take_fifth_of_num = cx.cplx([-28, 3])

print(cx.powFrac(take_fifth_of_num, 1/5))

1.6013 + 1.112i

As a check we have:

fifth_root_of_num = cx.powFrac(take_fifth_of_num, 1/5)

print(fifth_root_of_num**5)

-28.0 + 3.0i

Warning

Due to multi-valuedness of trigonometric functions, there are more fifth roots of \(z\) than what we calculated above. Four more in fact. These can be found through multiplying by (primitive) roots of nity.

Roots of unity¶

A famous equation among complex numbers is the equation for the unit,

for a given \(n\). From the fundamental theorem of algebra there will be exactly \(n\) solutions to the above equation, counted with multiplicity.

Note

In the case where \(n\) is a prime number, there will be \(n\) distinct solutions.

For each \(n\), any solution to \(z^n = 1\) is referred to as an \(n\)-th root of unity. The set of all \(n\)-th roots of unity forms what is known as a group. This is due to the following features:

if \(z_1, z_2\) are solutions, then \(z_1^n = 1\) and \(z_2^n = 1\). Note that their product \(z_1z_2\) will also be a root of unity,

if \(z^n = 1\) then \((1/z)^n = 1/z^n = 1/1 = 1\), so \(1/z\) is a root of unity;

the unit \(z = 1\) is itself a root of unity.

Roots of polynomials \(f\) (solutions to \(f(x) =0)\) often involve forming fractional powers of complex numbers. The operation of forming such powers is also known as root extraction - an essential part of the notion of a radical.

As we have seen above, there is an ambiguity here since there is no “single” root of a complex number. If any solution is known, multiplying it by powers of an appropriate root of unity recovers other solutions. In this way, roots of unity can efficiently allow for generating new solutions from old.

The function rootsUnity() in cplxnum.py passses integers \(n\) and returns a list of all \(n\)-rots of unity. For example, a list of all the \(7\)-th roots of unity is:

seventh_roots = cx.rootsUnity(7)

for rt in seventh_roots:

print(f"a root is {rt}. Its 7th power is {rt**7}")

a root is 1.0 + 0.0i. Its 7th power is 1.0 + 0.0i

a root is 0.6235 + 0.7818i. Its 7th power is 0.9999 - 0.0002i

a root is -0.2225 + 0.9749i. Its 7th power is 0.9998 - 0.0001i

a root is -0.901 + 0.4339i. Its 7th power is 1.0002 + -0.0i

a root is -0.901 - 0.4339i. Its 7th power is 1.0002 + 0.0i

a root is -0.2225 - 0.9749i. Its 7th power is 0.9998 + 0.0001i

a root is 0.6235 - 0.7818i. Its 7th power is 0.9999 + 0.0002i

Further application¶

Recall earlier that we calculated a fifth root of -28 + 3i. To find the other four, we can multiply the solution we found by any fifth root of unity.

Note

In fact, we would need to take a primitive root of unity. Any root (except the unit) to a prime will be primitive however. E.g., since \(5\) is prime, any \(5\)-th root of unity (other than 1) will be a primitive root.

Recall that we labelled the number -28 + 3i as take_fifth_root_of. We obtained a fifth root which we labelled fifth_root_of_num. The other fifth roots of -28 + 3i are:

fifth_roots = cx.rootsUnity(5)

fifth_root = fifth_roots[-1]

all_fifth_roots = []

for i in range(1, 5+1):

all_fifth_roots += [fifth_root_of_num * (fifth_root**i)]

print(*all_fifth_roots, sep = '\n')

1.5524 - 1.1793i

-0.6419 - 1.8408i

-1.9491 + 0.0416i

-0.5627 + 1.8665i

1.6013 + 1.112i

As a consistency check we can return the fifth power of each number in all_fifth_roots to ensure we indeed recover the original number -28 + 3i. And so, up to floating point error, we have:

for root in all_fifth_roots:

print(root**5)

-28.0015 + 2.9989i

-27.999 + 3.0022i

-28.0019 + 2.9992i

-27.9968 + 3.0003i

-28.0017 + 2.9987i

as expected.

Note

In this example we chose the fifth root of unity fifth_root = fifth_roots[-1]. We could of course choose any other (non-unit) fifth root of unity, e.g., fifth_root = fifth_roots[-2] or fifth_root = fifth_roots[-3]. This would return the same fifth roots of -28 + 3i, albeit in a different order.

Evaluation¶

With the arithmetic of complex numbers established, it will be possible to evaluate general polynomials on complex numbers. The appropriate method to call is cplxEval() on any instance of Poly. This method passes an instance of cplx and returns an instance of cplx.

As an illustration, consider the polynomial \(f(x) = 1 + x^2\). On the complex number \(i\) we have:

from class_scripts import polynomial as pnml

c_num = pnml.cplx([0, 1])

poly_to_evaluate = pnml.Poly([1, 0, 1])

print(poly_to_evaluate.cplxEval(c_num))

0.0 + 0.0i

Note

In the above code block we import polynomial.py from the directory class_scripts. And in class_scripts/polynomial.py we have the code from cplxnum.py. In order to run code from one script we write our complex number here as c_num = pnml.cplx([0, 1]) instead of cx.cplx([0, 1]) as in earlier parts of this document. Calling cplxEval() and passing cx.cplx([0, 1]) would result in a type error here.